A reader asks:

Ben attacks the people who pay off their mortgages early. Does this mean he’s a fan of the Trump administration’s 50-year mortgage idea?

US Housing Director says government is exploring 50-year mortgages:

Will it ever happen?

I don’t know, but that doesn’t stop me from crunching the numbers.

The initial reaction to this proposal was quite negative across the board. People in personal finance despise this idea.

Let’s look at the numbers to see why.

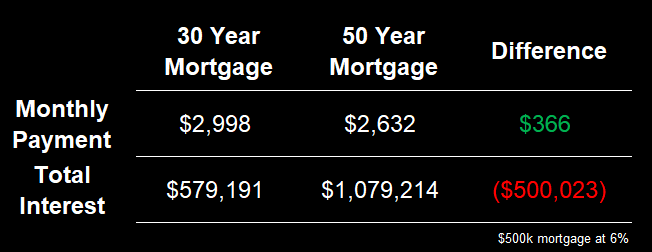

I like round numbers, so let’s look at a $500,000 mortgage at a 6% fixed rate over 30 and 50 years:

The monthly payment is slightly lower, but the lifetime interest paid is much higher.

Now let’s look at the monthly payment profile to see why a 50-year mortgage isn’t the best when it comes to building equity.

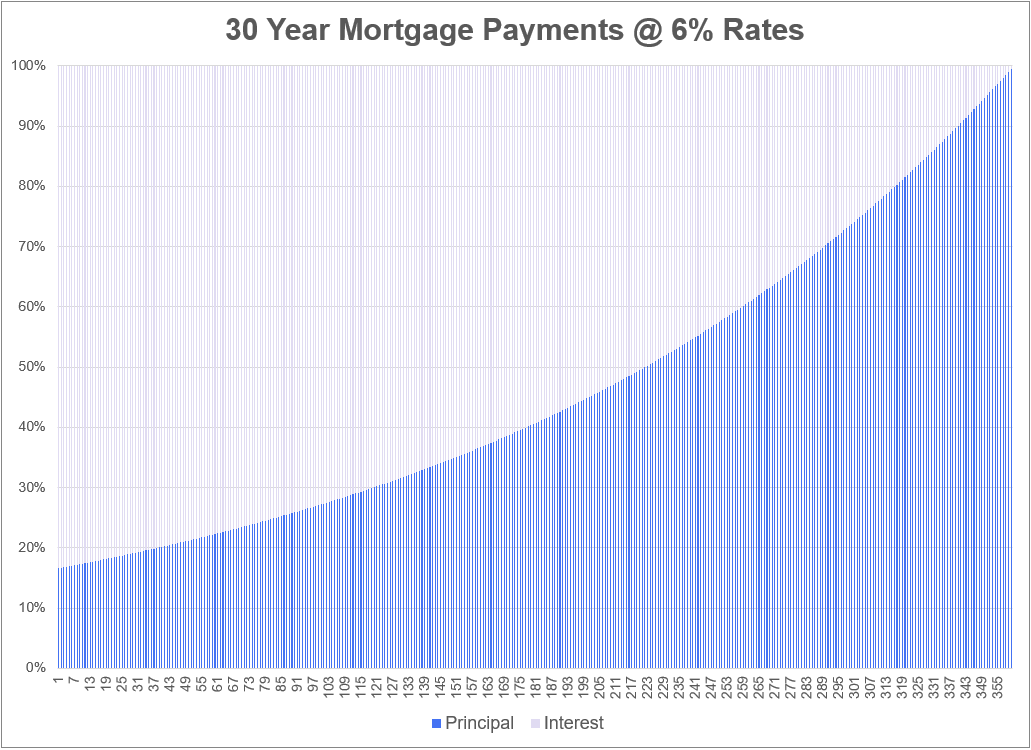

This is the payment breakdown between principal and interest for a 30-year mortgage at 6%:

Initially, you pay 83% of your payment in interest costs and 17% in principal repayment. This is how amortization works on a loan of this length.

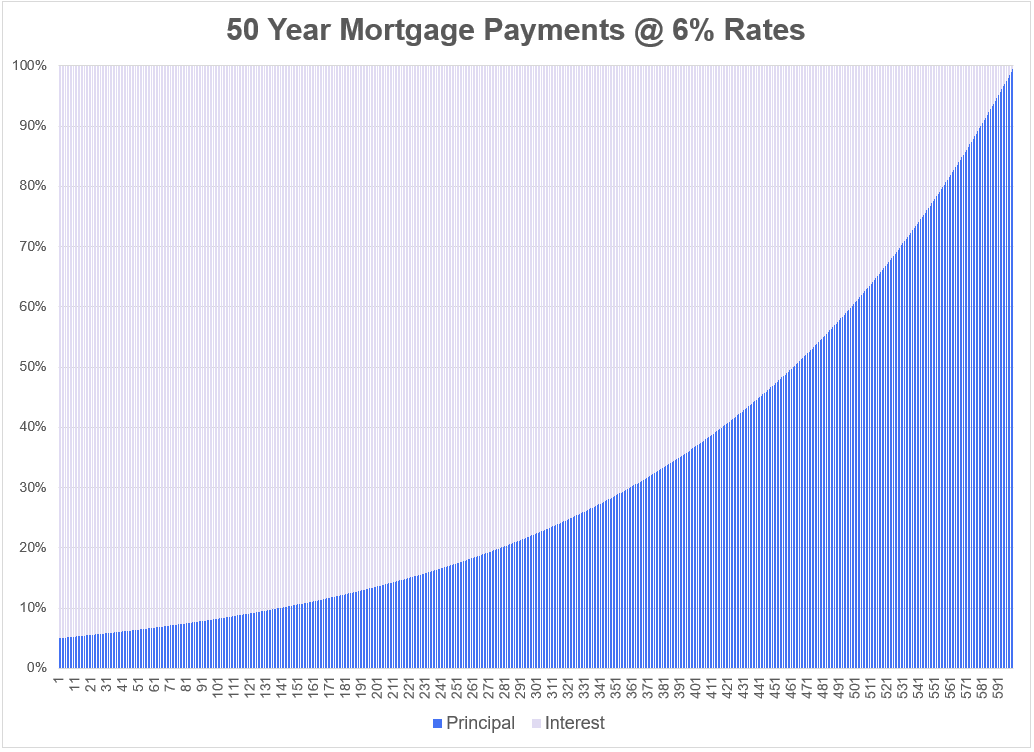

Now let’s look at the 50-year mortgage:

Basically, the entirety of your payment from the start – 95% – goes towards interest charges. It takes a very long time to make a dent in your principal balance.

After 10 years, this is the amount you would have in the home per mortgage term:

- 30 years: $81,571

- 50 years: $21,636

This is the biggest problem people have with a 50-year mortgage. Apart from the increase in house prices, you are not actually building up any equity.

And in this example, the same interest rate is used for both terms. Currently, the mortgage interest rate with a term of 30 years is roughly 0.5% higher than the mortgage interest rate with a term of 15 years:

You would assume that a 50-year mortgage would have a higher rate than a 30-year mortgage. In my simple example, if there were a 40 basis point spread between 30 and 50 year interest rates, you would only save $217 per month ($2,998 vs. $2,781).

It doesn’t move the needle significantly in terms of affordability.

That is the glass-is-half-empty principle.

Now allow me to play Devil’s Advocate.

No one stays in a house for fifty years. The average homeownership term in America is somewhere between 10 and 12 years. That’s why you should think of a 50-year mortgage as an interest-only loan that allows you to lock in the mortgage payment and hedge against rental inflation.

That’s not a terrible way to look at this, but it’s still not optimal. If the idea is to fix the housing market and make it more affordable for young people to buy, then this is not the answer. This is like a band-aid on a machete wound.

If we’re just going to throw ideas at the wall to see what sticks, here’s mine:

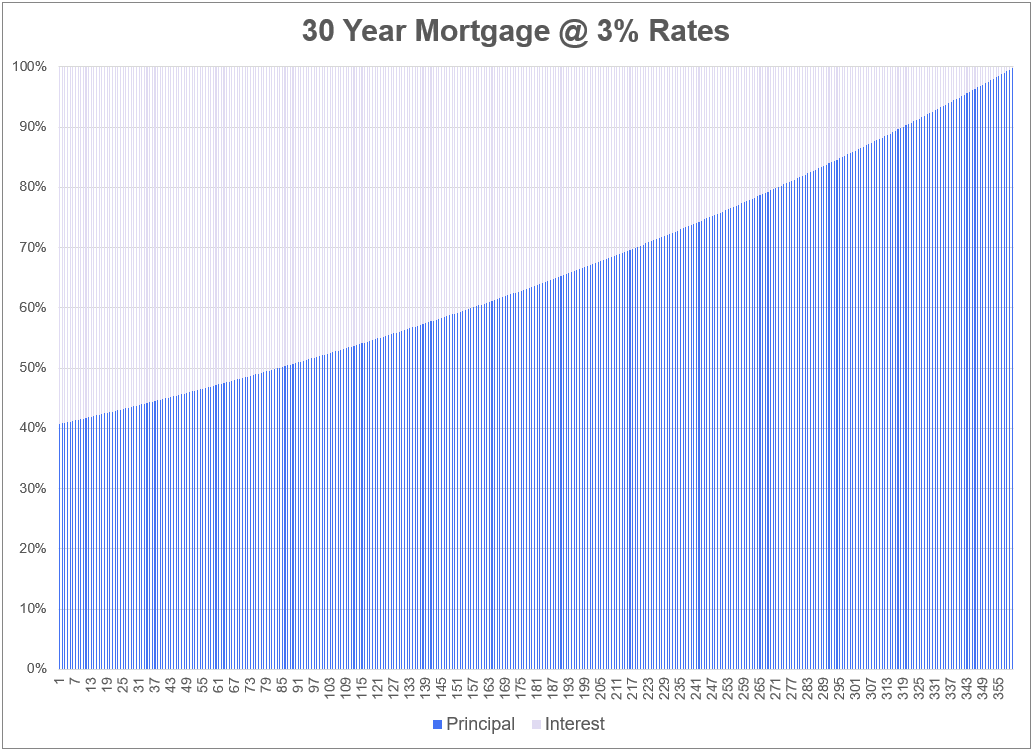

Why don’t we offer every starter on the housing market a one-off mortgage interest rate of 3%?

It’s not your fault if you missed out on generations of low interest rates in your early 20s due to bad timing in your stage of life. A lower mortgage interest rate would have a much greater impact on the finances of first-time homebuyers than mortgages with a term of 50 years.

Here’s the story of the tape for a 6% and 3% loan on a $500,000 mortgage over 30 years:

The monthly amount and the total interest paid are much lower.

Now look at the payment profile:

This is why a 3% mortgage rate is probably one of the best personal finance assets households have ever seen. You will receive a higher percentage of your payment as principal repayment than with a loan with a higher rate or a longer term.

The government, most likely Freddie and Fannie, would have to fund these loans. Or perhaps the Fed could buy mortgage-backed bonds to lower mortgage rates.

I know it doesn’t seem fair for the government to tinker with the housing market, but that is exactly how the middle class was built in the 1950s. The government guaranteed the homebuilders’ loans to take the risk off their shoulders. They offered VA mortgage loans to the soldiers coming home from World War II. They encouraged the construction of more homes.

Clearly, building more housing for everyone would be a much more desirable solution.

Increasing the supply of housing would significantly reduce the pressure on buyers. The federal government should encourage local governments to change their zoning restrictions to facilitate the construction of more housing without unnecessary red tape. If we are going to deregulate, housing is the most important.

Financial engineering is easier than building in the physical world, but building more homes really works.

Until that happens, we’re going to have to get creative unless we want all our young people to rebel because they can’t afford to buy a house.

We laid out this question in the latest edition of Ask the Compound:

Jonathan New of Ritholtz Chicago joined me on the show this week to discuss questions about the Kyle Busch insurance scandal, the sequence of return risk in retirement, asset allocation decisions, and learning versus earning early in your financial career.

Further reading:

Housing market Adel

#economics #50year #mortgage #wealth #common #sense