Sharing large production data sets is rarely a single event: it is a careful, step-by-step process. At Webflow, we’ve migrated hundreds of millions of documents from a vertically scaled database to a shard architecture using adapter layers, queues, and idempotent tasks. Here’s how we did it with no downtime or data inconsistency.

Over time, continued growth in data volume and throughput has exposed the practical limits of vertical scaling. Hardware costs rose, performance improvements began to plateau, and operational risk increased as clusters grew larger. In the case of Webflow, one of the maximum replica sets of our document cluster had a 4TB limit set by the vendor, which placed a hard ceiling on how far the cluster could scale vertically. That cluster served as a record system for much of the platform’s unstructured data, including site DOM, components, styles, and interactions, and the collections continued to grow steadily. While sharding was a known future requirement and progress had already been made in migrating location data, other investments in scalability and reliability were prioritized as part of a broader, multi-year evolution of the platform.

As the cluster approached the upper scale limits, those theoretical limits became tangible operational risks. Recovery from failures became slower and more complex, with increasing data volumes increasing blast radius and lengthening recovery timelines. What had once been a forward-looking scalability consideration became an immediate reliability issue. In response, we launched a targeted migration effort to remove the four largest collections from the document database, reducing its overall size by more than half and laying the foundation for the sharded architecture described in the remainder of this article.

Migration strategy overview

We evaluated several strategies for performing the migration, including big-bang, on-demand, and trickle approaches. Ultimately, we chose a droplet migration for a few key reasons:

- We had to maintain product stability and achieve zero downtime

- We wanted to validate the migration incrementally, with clear safeguards and rollback paths (spoiler: we didn’t need them)

- An on-demand approach was not feasible because many sites are inactive and would never naturally trigger a migration, making a full cleanup of unshardened collections impossible

To support a droplet migration, we have a adapter layeror an abstraction that allowed the application to remain agnostic about whether data was in the sharded or non-sharded database. This ensured that not all sites had to query the same database at the same time. The interface itself has also evolved, as querying the shard database now required a shard key.

For example, retrieving DOM nodes in the old abstraction looked like this:

import * as fullDom from 'models/fullDom'; // our DOM model module

// Fetch the DOM data from the page ID

// Assumes all page IDs are unique

const node = await fullDom.getPage(pageId); With the new approach it became:

import {DomAdapter} from 'dataAccess/dom/domAdapter';

import {DomGetPage} from 'dataAccess/dom/domDbAction';

// Asynchronously generate our adapter layer based on which DB it should call

const domAdapter = await DomAdapter.create(

siteId // our shard key

);

// Use the same parameters as before in a type-safe query API with a shard key adapter layer

const dom = await domAdapter.getPage(new DomGetPage(pageId));Under the hood is the DomAdapter layer was responsible for:

- Transparently determine whether to query the sharded or non-sharded database based on a site’s migration metadata

- Issuing sharded queries using the source’s parent site ID (site ID) as the shard key, which naturally aligns with access patterns since most queries are site-centric

Once adapter layers were installed for each collection, each call site had to be updated to use the new interface. Some migrations were simple; others required dozens of changes and the addition of thorough testing coverage to ensure accuracy.

Migration system

When this project was implemented, Webflow did not have a comprehensive system for large-scale data migrations. The standard approach was to set up a single, short-lived Kubernetes pod and run migration scripts for as long as necessary. Given the size of Webflow’s datasets, which often span hundreds of millions of documents and terabytes of data, this often resulted in a migration that took weeks, required manual progress tracking, and required constant operational monitoring.

As part of this initiative, we wanted to build something that could function at a significantly larger scale, with better observability, fault tolerance, and automation.

A new migration system, directly in the queue

Webflow already makes extensive use of Amazon SQS for asynchronous workloads such as site publishing and Generating AI sites. Over time, we’ve built abstractions and infrastructure that make it easy to define queues and batch workers for new use cases. Leveraging this existing system was a logical choice for large-scale data migration.

The main challenge was to efficiently queue tens of millions of jobs Send message batch is limited to 10 messages per request. To work around this, we implemented a fanout pattern using an additional SQS queue:

- An initial async request (

initFanoutRequest) queues a set of site IDs to be migrated - These IDs are grouped into batches and submitted as

fanoutBatchOfSitesjobs to a sharded fanout queue - Each batch is then split into individual site-level tasks and placed into a sharded migration queue

- Migration workers process these jobs and apply for jobs ETL logic to migrate data to the sharded database

Design of migration tasks

Each migration task was implemented as an idempotent single-responsibility task, migrating an individual site’s collection resources and updating the migration metadata used by the adapter layer to resolve the appropriate source of truth. The migration primarily performed a direct copy of non-sharded data, while selectively transforming certain identifier fields from string values to ObjectId types to improve storage efficiency and query performance, and adding the site ID shard key to better align with site-scoped access patterns. By isolating each migration task to a single site, migrations can be safely retried or resumed after interruptions such as restarts, timeouts, or deployments, without leaving a partial or inconsistent state.

Even after a successful migration, we retained a rollback mechanism as a safety net. This allowed a site to be returned to the non-sharded collection via the same fanout pipeline, restoring the original documents as the source of truth if validation or operational issues arose after migration. Fortunately, such a mechanism was never necessary.

Concurrency and data consistency

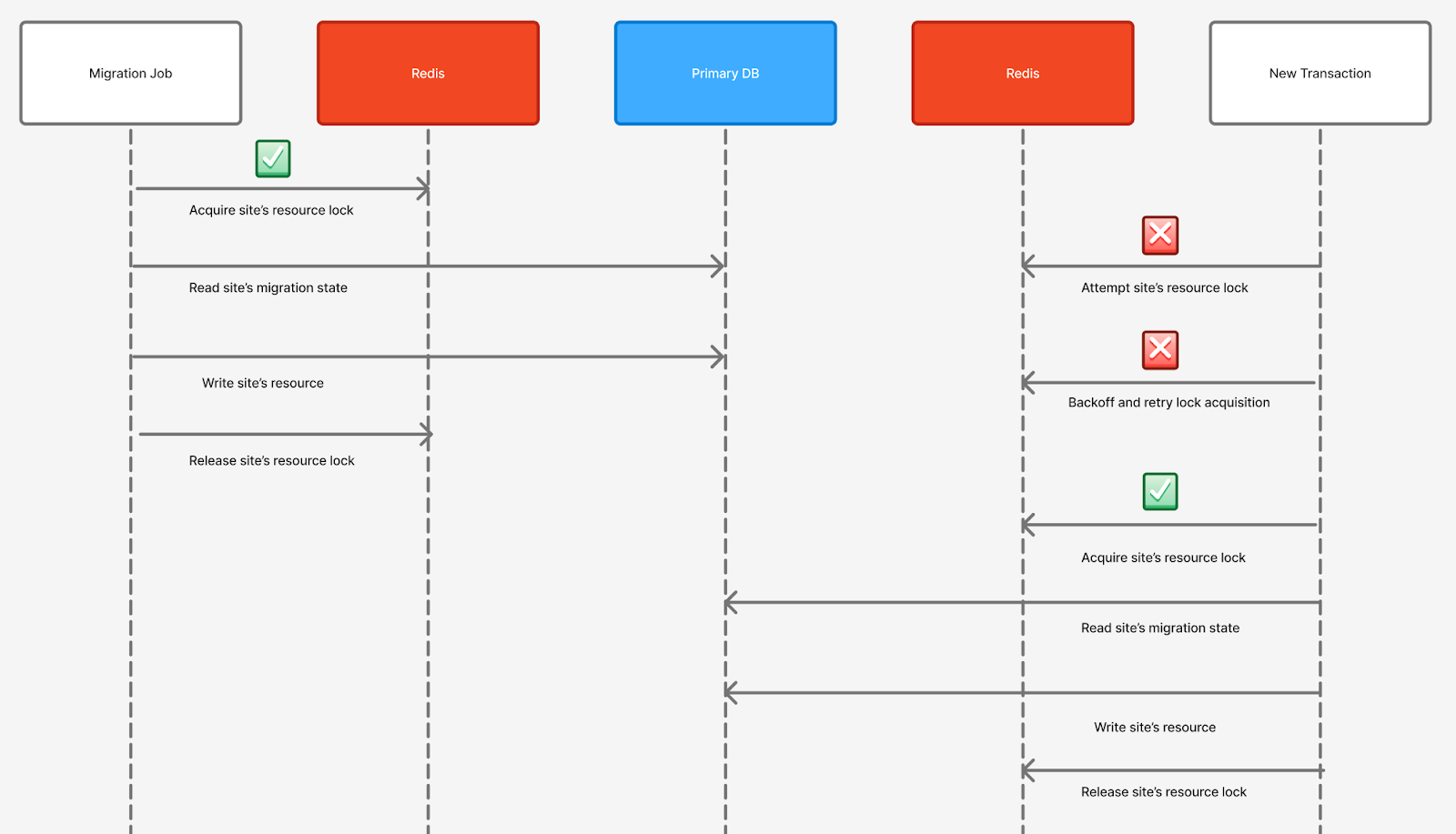

While the migrations were in progress, there was a risk of race conditions if another client tried to write to the same non-sharded documents. Without proper coordination, this could result in data corruption or inconsistency between competing transactions. To address this, we implemented a Redis-backed locking mechanism to ensure data consistency. The first write obtains the lock and subsequent writes until the lock is released. The scope of the lock was intentionally limited to only include the operations necessary to read migration state metadata and write the associated source data.

Locking comes with its own risks, including deadlocks and lock conflicts, which can degrade performance or cause serious outages. To minimize risk exposure, interlocks were only applied under narrowly defined, dynamically controlled conditions: a location ID had to be within a predefined ObjectId range, and the write path had to target the collection that was actively undergoing the migration. This essentially created a sliding window of site IDs that were eligible for locking at any time. Because the batch fanout design sends sites in ascending ID order and can be resumed from any checkpoint, we were able to target specific site ID ranges and limit the lock to a small, controlled subset of sites. The approach ensured strong consistency guarantees were maintained during active migrations, while tightly limiting the impact on performance and reliability on the broader platform.

Results and impact

The most immediate result of this project was a substantial reduction in the size of Webflow’s primary database. By extracting the four largest collections, we reduced the total data footprint by more than 50%, removing more than 2 TB of data and hundreds of millions of documents from the main cluster. This significantly reduced read and write throughput on the primary database, reduced operational risk by reducing blast radius and recovery timelines, and improved steady-state performance across the platform. Some collections have seen improvements in latency, ranging from 10% to 45% for core database operations. These gains were largely due to a smaller working set and reduced index pressure on the primary cluster, which reduced contention for shared resources such as CPU, disk I/O, and replica set coordination, and lowered tail latency for common read and write paths.

In addition to these short-term wins, the migration also confirmed the long-term benefits of horizontal sharding as Webflow continues to scale. We established internal sharding guidelines, removed the limitations imposed by a single database instance, and restored room for future growth. Equally important, the adapter layer created a repeatable blueprint for sharing additional collections, and the migration pipeline evolved into a migration-agnostic, proven framework that is now reused for other large-scale data migrations without disrupting production workloads.

#Scaling #vertical #boundaries #split #data #migrations #Webflow #Webflow #blog